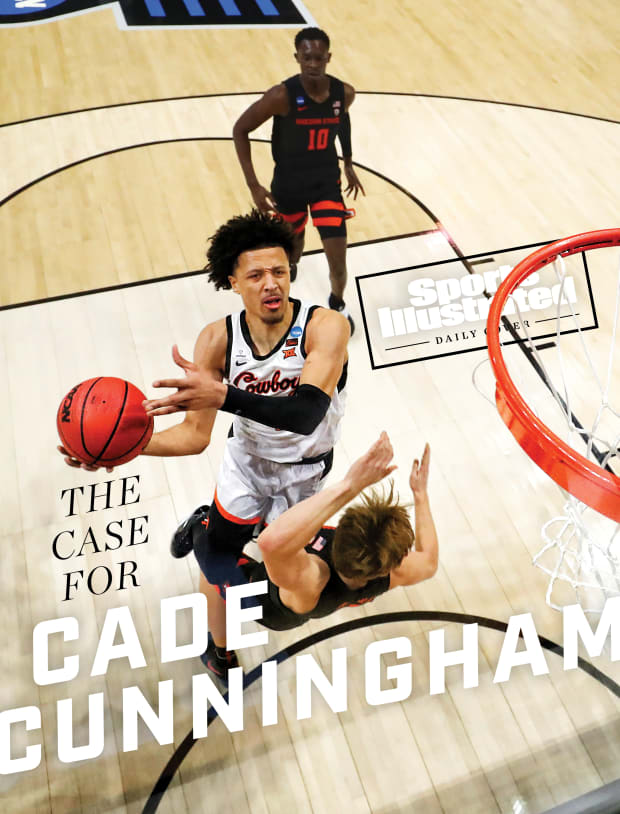

New on Sports Illustrated: Why Cade Cunningham Is the No. 1 Pick

It’s rare a prospect like Cunningham comes along, and even rarer to see one so comfortably ordained as the next big thing.

However many hours from now, Cade Cunningham will become the No. 1 pick in the draft. He’s ridden the wave of hype rail to rail, dominating with his mentality as much as his skills, more an outlier in the figurative, conceptual sense than the physical one, and certainly not in the statistical realm. It’s rare a prospect like Cunningham comes along, and even rarer to see one so comfortably ordained as the next big thing. Slap whichever adjectives and buzzwords onto him you choose; NBA teams have tried them on for size.

Cunningham has been pegged as the top player in his class for long enough now that it sometimes gets taken for granted. When that happens, you get nitpicked. Evan Mobley, Jalen Green and Jalen Suggs are in this draft, too. Even the Pistons are dragging out their decision process behind the scenes. While the quality of a draft requires time to properly ascertain, there’s near-unanimous agreement around the NBA that the prospects at the very top of this year’s class would hold water as elite talents in most years. There are debates worth having.

And yet, it’s Cunningham who will don his new cap first tonight. It will probably be a Pistons one. In the minds of many, he’s the clear-cut top dog. So it might be a different hat, but nobody’s expecting that. He might be Rookie of the Year this time next year, he might not. That scenario is still a pretty easy sell. He’s won basketball games everywhere he’s played his entire life, at every stop. That part of the deal might have to wait a year or two, but it’s probably coming. And frankly, there’s not much reason to expect anything else.

“Cade is a game-changer,” says one NBA general manager. “Rarely can someone wear the crown the entire four years [of high school] and freshman year [of college]. He has.”

If you’ll allow the author a brief interlude: The first time I can vividly remember being struck by Cunningham’s game was actually the third time I saw him play, on April 4, 2019, in New York City at the GEICO Nationals. His Montverde Academy team faced off against Fort Lauderdale University School, led by five-star recruits Scottie Barnes and Vernon Carey Jr. This was his first year at Montverde, the famed pro prospect factory outside of Orlando, where he’d transferred from Bowie High in Arlington, Texas, looking for a steeper challenge.

At that point Cunningham was already a consensus top 10 prospect nationally, with notable size, prodigious feel and playmaking skills, but he hadn’t yet entered the conversation as the top player in the class. Green and Mobley, based in California, held top billing on most recruiting sites. Cunningham played 15U and 16U with his Texas Titans AAU squad, choosing to stay with his age group and teammates rather than skip steps, as many elite players do. He was still proving he could play point guard full time. Montverde and its esteemed coach, Kevin Boyle, let him do it. While watching him bring the ball up the floor, his body type, passing vision and unwavering calm were immediately striking.

“He kind of always played the same role for his teams, but the more we saw him play, the more we started thinking, Oh, wow, he can actually be a primary ballhandler,” says Eric Bossi, national basketball director for 247Sports. “Sometimes we see kids in high school who are that size and can handle the ball, we just label them as small forwards. We see a lot of guys try to be point guards, but it’s usually hard to take that to the next level. We’ve all been sold that a million times, and it’s not always true. So [Cade] had to prove it to people a little bit.”

Single-elimination tournament games are few and far between at the high school level, but they do tend to be good evaluation settings, if only to get a sense for how young players respond in pressure environments. Cunningham, a junior on a team headlined by McDonald’s All-American Precious Achiuwa, passed that test in all respects. In a meeting of two relatively even teams, Cunningham grabbed the reins early and often, running the offense as an oversize point guard with the poise of a much older player.

Points and assists are nice, but the most valuable, finite resource in a basketball game is time. Most teenage guards have little to no concept over how to dictate pace, as it’s typically a learned habit that requires trial, error and unwanted losing. The game was never truly out of hand score-wise, yet it still felt out of reach somewhere in the third quarter. Montverde began to generate stops and pull away, Cunningham’s clinical guard play putting a stranglehold on any opportunities for circumstances to change. His methodical efforts contributed to a 17–0 run late in the game, and eventually a decisive eight-point win.

There was never one moment or play that screamed Future No. 1 pick. But clearly, Cunningham was the most impactful player on the floor. So, I remember being stunned by the the postgame box score: he’d finished with just four points on six shots, eight rebounds and one assist. By his standards, he didn’t even play especially well, which was the startling thing unto itself. But his willingness to make the simple play, and his iron grasp of the game’s tempo, was unmistakable.

There is a certain dissonance between the eye test and the box score when evaluating ballhandlers, as it can be near-impossible to quantify the way a player makes decisions, particularly at the lower levels of basketball. When scouting teenage prospects in games that are almost always mistake-prone and sloppy, you can argue that box scores hardly matter, and that tendencies and intentions mean far more than a play’s result. Numbers matter, but there are things they miss, like the ability to win a game for your team without really needing to shoot the ball. “Sometimes [Cunningham’s impact] is hard to describe unless you’re actually there watching him,” Bossi says. “And then it’s like: Oh yeah, I get it.”

The NBA zeroed in heavily on Cunningham later that year, following a series of strong sessions on Nike’s spring EYBL circuit, where he was named MVP and emerged as a much more dangerous scorer than ever before. His star took off that summer at the 2019 FIBA Under-19 World Cup, where he flashed a vast array of skills despite shooting just 40% from the field, making just one of 14 threes. Again, it was his ability to lift others up and improvise in game flow that shined. He shared a backcourt with another savant-like guard, Tyrese Haliburton, at the center of a loaded U.S. team that also included Green, Mobley, Suggs and Barnes. They ran the table on the way to gold.

On Nov. 5, 2019, shortly before his senior season began, Cunningham committed to Oklahoma State, which had already hired his older brother and trainer, Cannen, as an assistant. Cannen, who played college ball for Larry Brown at SMU and briefly played pro overseas, had been more or less responsible for Cade’s individual development for much of his younger life, including the transition from playmaking forward to jumbo pick-and-roll guard in the middle of high school. Oklahoma State coach Mike Boynton recruited Cade earlier and more aggressively than any other team, showing face at games with next to no fans when Cunningham was a 15-year-old freshman. Cliché or not, the Cowboys felt like family. And Cade maintained his commitment after the NCAA imposed a postseason ban on the program.

Cunningham’s senior year at Montverde became the stuff of legend, with industry experts widely wondering whether the Eagles and coach Kevin Boyle had built the best high school team ever. Four of that team’s starters—Cunningham, sharpshooter Moses Moody and transfers Barnes and Day’Ron Sharpe—will hear their names called in the first round Thursday. Two more blue-chip prospects—Caleb Houstan and Dariq Whitehead—played supporting roles as underclassmen. The results were staggering, and Montverde finished the season 25–0.

“They weren’t just freak athletes who could pound everyone into submission,” says Bossi. “They had freak basketball players, too. High IQ, smart guys, guys who spent hours in the gym and were totally dedicated to things. They were selfless, and there was no real ego. ... It’s pretty special that those kids were able to get along the way they did.”

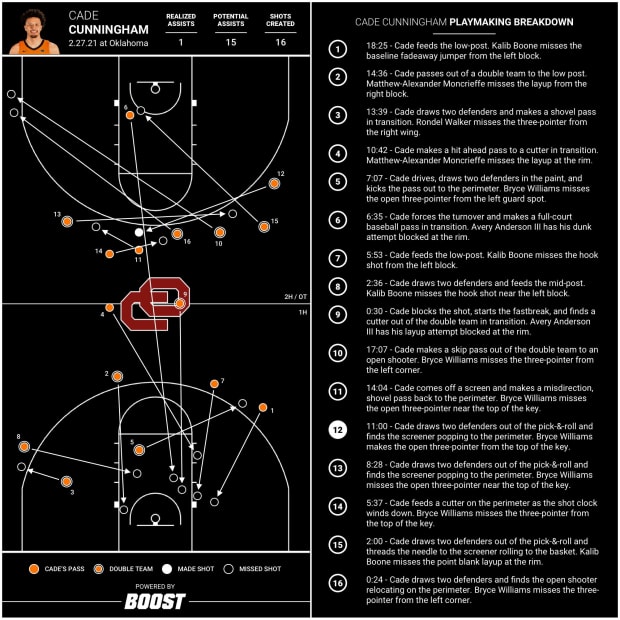

As far as the No. 1 pick is concerned, there may be no stronger case for Cunningham than the events of Feb. 27, 2021, when the Cowboys traveled across the state for the season’s first meeting with archrival Oklahoma, a consequential game in the Big 12 standings. That night would stand as the most impressive of Cunningham’s 27-game college career, and a touchstone of his candidacy as the No. 1 pick. Cunningham again steered the ship, finishing with 40 points in 44 minutes, including 10 in overtime. He shot 12-of-21 from the field, grabbed 11 rebounds, blocked two shots and stole the ball three times. He was everywhere all the time. His upside as a prospect was on full display. The only snags were his six turnovers—a byproduct of his immense workload—and the fact that he finished with just one assist.

One of the flaws of a standard box score is that it often fails to quantify opportunities that are missed. Assists and assist rate are far from the only measure of a player’s passing acumen, yet they are often at the center of public discourse surrounding the quality of a playmaker. Critiques of Cunningham often stem in that direction: While he was billed as a true point guard, he recorded 94 assists and 109 turnovers in his 27 college games, subpar numbers for any first-round prospect, let alone a No. 1 pick.

Boost Technology’s AI engine, which delivers valuable player tracking insights, allows us to dig a little deeper. While the concept of an assist (a pass that leads directly to a make, as designated by an official scorer) isn’t everything, the potential assist—defined here as any pass that leads to a missed shot—can tell us more about the volume of chances a passer creates. According to Boost’s data, Cunningham averaged 3.5 assists per game, 6.4 potential assists and 1.2 secondary assists (defined as passes preceding a team assist) over the course of the season. Before nitpicking his assist-to-turnover ratio too deeply, consider the opportunities that were missed.

In that particular Oklahoma game, where Cunningham’s single assist could be construed as a negative, he actually recorded a season-high 15 potential assists, all of which can be seen below.

While not every pass Cunningham made on the chart below would have been guaranteed to be scored as an assist had the ball gone in, the key element here is the quality and variety of his chance creation. He throws bounce passes, push-passes and lobs, varies his zip on the ball as needed, and deftly reads pressure in the half court. His quarterback-style overhand throws hark back to his youth football days. He can distribute with either hand. Outcome aside, the ball frequently ends up where it needs to go. It’s a package of strengths that promises to play up in the NBA, when deployed in concert with the best players in the world. Whether the ball goes in the basket is not the point. And don’t forget Cunningham added an efficient 40 points by himself, on top of everything else.

“Your knee-jerk reaction [with passing] is always to see how many assists a guy averaged,” says one Western Conference executive. “It’s different when you want a guy to be selfless, but there aren’t that many great options on the team. I don’t care to try and quantify it a certain way at the college level. That’s where the eye test comes in—you can see if a guy really can pass. I hate to make it that simple. It’s fair to go back and see how selfless [Cunningham] was in other venues. His season shouldn’t erase what you thought about him prior to college.”

The help wasn’t always there, but it wasn’t always the Cowboys’ fault, as opposing teams game-planned heavily to stop Cunningham all season and took their chances with the other players. He led the Big 12 in minutes and scoring, anyway. “No one else on their team could beat you alone,” said one opposing Big 12 staffer. “Only Cade.” Cunningham attempted 27% of the team’s 573 total three-point attempts and made 40% of them, answering the lingering questions about his jumper. He emerged as a lethal off-dribble shooter, with an expanding range of moves that utilize craft to separate from defenders he can’t simply run away from. It’s not flashy, and he’s not a jaw-dropping athlete. But when something earns you comparisons to Jayson Tatum, you take it.

Oklahoma State still came in just 155th among Division I teams in offensive efficiency, averaging 1.03 points per possession, per Boost data. The team’s second- and third-best shooters, Avery Anderson and Bryce Williams, shot 33% and 32% from three, respectively. Accordingly, they were 291st in the nation in three-point frequency, despite playing at the 43rd-fastest pace. The Cowboys were successful anyway, finishing 21–9 and 11–7 in conference, and were one of two teams to beat eventual national champion Baylor. They earned a No. 4 seed in the NCAA tournament, with the school’s appeal process allowing the team to participate.

In the middle of the season, Cunningham agreed to play more away from the ball so that the team’s second-best player, Isaac Likekele, could play his natural position at point. Still, to win games, the offense had to run through its best player. So the Cowboys’ half-court attack became predicated on a series of fake actions designed to set Cunningham up in pick-and-roll, post-up and isolation spots. There were times he was too deferential, and stretches when he took over. Opposing teams mixed and matched looks and applied heavy ball pressure in an attempt to keep Cunningham out of rhythm and force mistakes. He still managed a respectable 57.4% true shooting percentage on nonegregious 28.1% usage. He scored in the 87th percentile in isolation, according to Synergy Sports. While often nitpicked for his finishing, he shot 62% at the rim, according to Barttorvik.com, though didn’t get there quite as much as you’d hope. The high traps and double teams he drew nightly certainly didn’t help.

There are still holes when you look at the numbers, but you have to want to find them. High-usage guards often struggle with turnovers as a byproduct of volume. It’s exceedingly difficult to envision a teenage player so consistent, intelligent, and so historically adjacent to winning basketball simply falling on his face as a professional. Understanding the context doesn’t guarantee Cunningham ever makes an All-Star Game, but it does help ease any lingering concerns about his college performance, his passing and his long history of making good choices on the floor.

Cunningham arrives in the NBA at a time when the definition of what makes a point guard is perhaps more fungible than ever. There are teams that play two lead ballhandlers together. Taller playmakers are en vogue. Mostly, teams let offense flow freely through their best players. Positions are defined more on the defensive end, by who a player can guard, than by what his precise offensive responsibilities are. The lines between the traditional five positions are blurry, and some would argue, irrelevant. The broad philosophy the majority of teams have come to share is simple: Let the best decision-makers make most of the key decisions with the ball. (And preferably surround them with as many shooters as possible.)

“Cunningham’s a modern wing player: He has feel, a quick mind, can score on his own and involve other players at the same time,” says one Eastern Conference scout. “He’s a positionless player in a positionless game. He’s an above-average passer for his size. He just has the innate basketball skill. I don’t want the ball in his hands the entire game, but that’s fine, the way the league is now. He has the foundation.”

While generally not projected by scouts to defend smaller ballhandlers in the pros, Cunningham’s size and anticipation skills make him viable at multiple positions within a scheme. He’s an excellent team defender and verbal communicator. He sets screens and boxes out and commits to the small things, with or without the ball in his hands. In a bigger-picture sense, that ability to play alongside anyone makes it much easier for a front office to add pieces around him and explore different avenues in building a championship-caliber team.

Consider NBA stars like Giannis Antetokounmpo, Zion Williamson and Ben Simmons, three uniquely dominant talents who require specific personnel around them to maximize their skills. For Antetokounmpo to have space to evolve as a playmaker, the Bucks had to bring in a three-point shooting center, Brook Lopez, alongside him. Cunningham, at 6' 8" with a multi-positional brain and a reliable jumper—sits on the other side of the spectrum. His simple presence opens up possibilities.

“When a player has that great versatility and NBA readiness, you just figure out the other s---,” the Western Conference executive adds. “You gotta keep that guy on the floor. And if it so happens he can run your offense, great; that’s almost like a bonus. I don’t think you pencil [Cunningham] in that way, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he ends up morphing into that.”

It’s hard to envision a five-man lineup Cunningham can’t make better. The beauty of the whole thing is that it may not matter what position he plays, so long as he plays. It's not always flashy. His ability to knock down shots and create for himself is expanding. He sees the whole floor, from all over the floor. The ball goes to the right place pretty much all the time. The malleability of his game is a feature of the package, not a footnote. He’s earned his spot atop the draft.

More NBA Coverage:

• NBA Mock Draft 6.0: Dust Settles on Top Three

• NBA Draft Big Board: Final Top 80 Rankings

• NBA Free Agency Rankings

Comments

Post a Comment