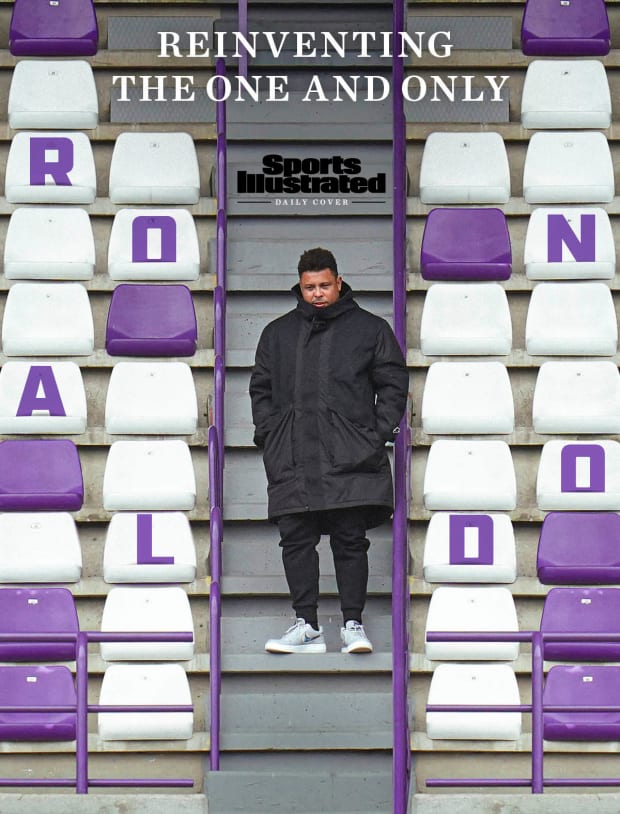

New on Sports Illustrated: Reinventing the One and Only Ronaldo

The Brazilian great went from mononymic majesty to just another guy with a familiar handle. Now he’s making a new name for himself in La Liga—as an owner.

In the summer of 1999, at the Nike headquarters in Beaverton, Ore., two galácticos of their respective sports met for the first time. Michael Jordan was 36, a year removed from winning his sixth and final NBA title. Ronaldo was 22, already a two-time world player of the year and making a case as the most feared striker in history. More than two decades later, Ronaldo can’t help but smile at what His Airness shared with him that day. “He said to me, ‘You are the Michael Jordan for soccer,’ ” Ronaldo recalls. “I was like, ‘Whoa, that’s a big compliment.’ ”

When Zeus invites you to Mount Olympus, you accept. And Ronaldo fit the part. At the height of his powers he mass-produced goals with breathtaking force, faster-with-the-ball-than-without-it speed and Promethean skill. These days, a cottage industry of social media videos devoted to 1990s soccer ensures the modern generation will see Ronaldo’s greatest hits. At least one 44-year-old Brazilian indulges, too. “I love to watch all of them,” says Ronaldo, “but there is one I love the most. Some guy made a video with me doing 256 caños”—nutmegs—“in my career. I can’t even remember that I did so many!”

Soccer fans will always wonder what Ronaldo could have achieved had he not suffered a pair of debilitating right-knee injuries that wiped out two years in his prime, at the turn of the century, and ever so slightly dulled his explosiveness. But it’s a measure of the man that he came back to lead Brazil to the 2002 World Cup title—with eight goals, including both in the 2–0 final victory over Germany—and finish his sterling 18-year career with 414 goals for country and club, which included stops at Barcelona, Inter Milan, Real Madrid and AC Milan. Along the way he redefined the center forward position, able to beat defenders one-on-one, shoot from distance, hold the ball up, serve as the first line of defense and drop deep to help teammates. If he hadn’t quite equaled Michael Jordan’s exploits, he wasn’t too far behind. Where does Ronaldo rank, all-time, among pure strikers? Most pundits say right behind Pelé. Most, but not all. Says AC Milan’s Zlatan Ibrahimovic, who’s right near the top himself: “Ronaldo Fenômeno is the best. Ever.”

What’s in a name? Well, if the name is Ronaldo and the topic is soccer, things can get a little complicated. Going back to 1996, three different Portuguese-speaking men with that moniker have won the annual award given to the world’s best player. There’s Cristiano Ronaldo dos Santos Aveiro (five times), the Portuguese force of nature who’s still plying his trade for Juventus at 36. There’s Ronaldinho, born Ronaldo de Assis (two), the now 40-year-old Brazilian maestro who reached his zenith at Barcelona between 2004 and ’06. And there’s our Jordan-endorsed Ronaldo Luis Nazário de Lima (three), who through no fault of his own went from the mononymic King of the World to not even the most famous Ronaldo in his own sport.

It’s uncanny. Imagine if there had been three generational inventors in the same era, each named Edison, each requiring a differentiating modifier. (“Ah, you mean light bulb Edison!”) So dominant is Cristiano Ronaldo in today’s global discourse that referring to the eldest Ronaldo requires complicating the majestic one-named simplicity that he once enjoyed. And so he’s described as Brazilian Ronaldo. Or Ronaldo Fenômeno (the Phenomenon, his old nickname). Or R9 (his number). Or perhaps, best of all, OG Ronaldo. (There are also a few less-kind modifiers that nod to the added kilos he put on late in his playing days.)

Ronaldo, though, views the nominal convergence with remarkable equanimity. “The coincidence is amazing, that so many Ronaldos are very good,” he says. “It is kind of a lucky name.” Whereas Cristiano Ronaldo’s parents named him after Ronald Reagan, OG Ronaldo’s family christened him after the delivering doctor at a Rio de Janeiro hospital. “The doctor did it for free because my parents couldn’t pay,” Ronaldo says. “Finally, my father brought him three kilos of shrimp that he gathered at the beach, and then my parents gave me the name of the doctor.”

Surprising as it sounds, OG Ronaldo is hoping to make a new name for himself. After retiring as a player a decade ago, he could have gone on permanent vacation at any of his homes in Madrid, Ibiza or São Paulo. (His four children, ages 10 to 20, whom he visits regularly, all live in Brazil.) He could have counted all the money he’d invested, building a business portfolio that includes the Brazilian arm of the Octagon talent agency (which also represents this writer), plus R9 Family Office, which helps pro athletes plan their finances. And he could have continued taking far-flung adventures, such as his 2015 trip to the Burning Man festival in Nevada with his girlfriend, model Celina Locks. “It was fantastic, a lot of art and music and 70,000 people in the desert,” he says with a giggle. “When we decided to go, they suggested we watch Mad Max. So I bought clothes like Mad Max.” His Instagram post from the Black Rock Desert—riding a Segway, wearing reflective heart-shaped glasses and a camo scarf—drew more than 73,000 likes.

But Ronaldo wanted to work, to immerse himself again in soccer. Coaching wasn’t on his wish list; too much job insecurity, and he preferred to manage four or five people, not 25 players. In 2014 he sampled ownership with the Fort Lauderdale Strikers, buying a minority stake in the second-division NASL team. He wanted to bring the Strikers up to MLS, the U.S.’s top flight, and met with commissioner Don Garber in New York City. “I told him: We want to join MLS, but we don’t have the $100 million,” Ronaldo says of the franchise fee at the time. “I said, ‘It’s better that you [adopt] promotion and relegation to improve football in America.’ And he said, ‘That’s not working here.’ He was glad to hear from me, but at the end he just said, ‘If you want to join us, pay the franchise fee.’ After that meeting, I started looking for new opportunities.” (A spokesperson for MLS denies Garber said this.)

One such opportunity came right after the 2018 World Cup. For €30 million ($36.1 million), Ronaldo bought a majority stake in Real Valladolid, a 92-year-old Spanish club (located in a wine-growing region northwest of Madrid) that over the years has yo-yo-ed between that country’s first and second divisions. The move puzzled soccer observers. Why would one of the sport’s greatest athletes buy a team in constant danger of relegation? Maybe the answer has something to do with a certain former NBA deity who 15 years ago took on the challenge of owning a middling franchise in Charlotte. Two decades after hearing it for the first time, Ronaldo is, in some ways, the Michael Jordan of soccer again.

“I love it,” Ronaldo says of being an owner. (Just as Jordan was the first former player to own a majority stake in an NBA team, Ronaldo was the first to buy a club in one of Europe’s top leagues.) “My energy is emotion. I was my whole life living football, so I’m not looking for other things to do. It’s what I want to do and what I know how to do. And that was why I bought a team.”

You wouldn’t ever see Michael Jordan in a scene like this. On a pre-pandemic Saturday afternoon in Castile and León, Spain, Ronaldo is enjoying a pregame coffee alongside friends at a humble outdoor cafe with red plastic tables, amid all the fans gathered to watch Real Valladolid II, the club’s second team, full of teenage prospects with aspirations for the Show. Only a couple hundred supporters make it to the B-squad stadium, near Valladolid’s much larger Estadio José Zorrilla, and many of them appear shocked to find Ronaldo, who smiles for pictures. For such a low-stakes game, the star power is off the charts. Before the opening whistle Ronaldo decamps to a field-level bench, where he sits next to Júlio Baptista, a former standout for Real Madrid and Brazil, and now a youth-team coach at Valladolid. Twenty feet away, on the opposing bench, is Real Sociedad B coach Xabi Alonso, another former Real Madrid star and a 2010 World Cup champion with Spain.

They’re all putting in the work. Few in this soccer-mad country will pay attention to the result—a spirited 2–1 win for Valladolid—but that’s not really the point. When you’re not a powerhouse club, like Barcelona or Real Madrid, you can’t just spend $60 million to add an established star. You have to develop your own.

“It was a beautiful match, very hard. But we played well,” Ronaldo says afterward, seated in a school desk inside the club’s bare-bones media room. “We invest almost €2.6 million [$3.2 million] in the second team. It’s a lot for the category. But it’s all young players and potential for the first team. . . . That’s our challenge, and so far we are happy with the results” (which have included 19 players ascending to the first team since the 2018–19 season).

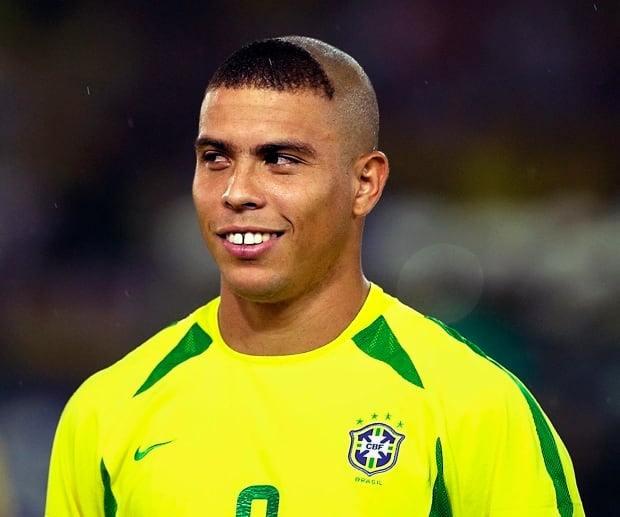

For someone whose physical presence was once other-worldly, Ronaldo is a lot more relatable these days. He wears a black polo with sunglasses tucked in the collar and dad khakis. His high-and-tight coif is bushy on top, a far cry from the shaved head he used to sport—or the infamous Star Wars–cantina tiara of hair he wore in the 2002 World Cup final in Japan. He’s sensitive to what people say online about his weight gain—“You cannot control people,” he says—which in some ways makes him even more approachable.

One reason he wants to shed some of those kilos: He’d like to play soccer again. He hasn’t for almost three years, because every time he stepped on a field he hurt himself. “In my head, I think I still can do it,” he says. “And when someone gives me the ball two meters over me, my head thinks I can arrive to it—and that is the big mistake, because I can’t. There are sometimes good matches for legends, and I want to be part of those.”

Ronaldo lives primarily in an apartment in Madrid—he sold his house to Real Madrid captain Sergio Ramos a few years ago—and he has set up a commercial office for Real Valladolid in the Spanish capital. When he bought the club, he brought on a few trusted associates, including David Espinar, a board member and cabinet director who serves as Ronaldo’s right hand. Espinar had been working as a journalist for the Madrid-based newspaper Marca when he met Ronaldo in the mid-’90s, as the Phenomenon was emerging on the global scene. He covered the star for the next decade, until the day in 2004 when Ronaldo showed him a Washington Post story that posited the Real Madrid striker was the world’s third-most recognized person, behind the Pope and President George W. Bush. “I need someone to handle this for me,” Ronaldo told Espinar, who became his personal communications director until he returned to Brazil to finish out his career with Corinthians in 2008.

When Ronaldo bought Valladolid, he put together a presentation for the club’s supporters and highlighted four words: revolution, social, competitiveness and transparency. Wait, revolution? “Ronaldo wants to demonstrate there is another way to deal with football,” Espinar explains. “He has seen what is good and what is bad, and he wants to manage the club in a way that takes the people into account. We are making football more democratic.”

Owning a mid-level Spanish soccer club is a little like being the mayor of a Rust Belt city where the first order of business is fixing the potholes. Ronaldo’s new regime publicized an email address, conecta@realvalladolid.es, and encouraged fans to communicate their questions, suggestions and concerns. The club promises to respond within two days, and Espinar says that more than 3,000 messages have been processed in the past two years. In one early test of the system, in 2019, the new management announced a price increase for the club’s 22,000 season-ticket holders, only to rescind it after many of those patrons expressed their displeasure through the email channel.

Ronaldo has since paid off the club’s main debt, around $25 million, and he and his brain trust have started a revamp of Valladolid’s physical plant. “We are a first-division team, but we don’t have the infrastructure that we believe we need,” Ronaldo says. “So we have to make a training facility for the club, for the first team, for the youth academy.” As the team scouts potential sites, so too begins a four-phase refurbishment of the stadium, which has barely been updated since it was constructed for the 1982 World Cup, replete with a field-encircling moat, to separate players from fans. Shortly after Ronaldo’s arrival, the team filled in the moat and updated the VIP lounges and locker rooms. Valladolid plans, too, to overhaul the stands and eventually install a partial roof, for a total cost of some $50 million.

Ronaldo mostly works from the Madrid office but takes at least two days each week to drive up to Valladolid (the Waze app helps him avoid speed traps, he says with a smile), where he attends every first-team game, some second-team matches and the occasional training session. “I’m kind of involved in everything,” he says. “I want to be close to the players and see what they need, but I try not to get too close, to stay in my place. I don’t want to be the president that says, I want this and that, otherwise I kick you out!”

“He’s always thinking about things,” says Espinar. “He asks for a regular report on season tickets, types of grass . . . on the Conecta [email complaint box]. He reads everything.” Truth be told, there’s a lot of work to be done. “Around 84% of our revenues come directly from TV rights,” says Espinar. “We have only 9% from commercial rights and 5% from ticketing. We need to get more sponsors, more partnerships.”

Ronaldo’s ultimate goal, about which he is transparent, is to sell Real Valladolid for a profit, but not for four more years at least, and not until his group has taken the club to a new level. For him, that means fighting to win trophies and eventually earning a place in European competition. “I’m not going to stay here forever, because I have other things for the future in my mind,” he says. “But it’s too early to talk about that. I want to make this club much better and bigger than when I got it. After that, let’s see. For now, it’s just: Keep working and keep the club in the first division.”

That last part is no small task. Ronaldo evangelized promotion and relegation to MLS’s leaders, but while that system incentivizes investment and competition, it also makes life less secure for an owner, who earns far more if their team remains in La Liga. All of Ronaldo’s plans for Valladolid involve staying in the first division, but his club has spent most of this season around the relegation zone. Survival is not easy when you cap your team’s total salary expenditure at €32 million ($38.9 million), and when competitors like Barcelona (up next on the schedule, April 5) and Real Madrid are spending upward of €600 million ($730 million). The prospect of the drop “is a very new situation for me,” says Ronaldo, who never came close to being relegated during his playing career. “I have to confess that I suffer a lot in this situation.”

While the pandemic has been hard on everyone, Valladolid has continued to pay all its employee and player salaries. Ronaldo says the television revenue helped limit losses to €6 million ($7.3 million), mostly from the absence of gate receipts—a big hit, but not ruinous. Those stadium and training facility improvements? They’re on hold but expected to resume on the other side of the virus. “We just miss our fans in the stadium,” says Ronaldo.

Like so many others around the world, though, Ronaldo’s most challenging moments this past year have come outside of work. Around Christmas he visited his family in Brazil, where both his parents, Sonia and Nelio, were hospitalized with the coronavirus for three weeks. “They’re safe now, but the last two months we had very difficult times,” he says. “So we all hope this year is going to be better.”

Back when fans could still attend games, before the pandemic, it was common to see supporters wearing Valladolid’s distinctive violet-and-white jerseys with RONALDO splashed across the back. It made sense. They were excited about having one of history’s greatest goal scorers on their side.

Ronaldo can’t blame them. “I love all my goals; they’re like my babies,” he says. But a favorite? “I always choose the two with Brazil against Germany in the 2002 World Cup final. They weren’t the most beautiful, but it was [their] importance. Two years before that”—following his knee injuries—“nobody believed I could play football again. I was the top scorer, and we won the World Cup. Those two goals represent my big fight for two years.”

The ridiculous haircut Ronaldo wore that night in 2002 is another story. “Horrible!” he bellows. “I apologize to all the mothers who saw their kids make the same haircut.” But, as he explains, there was a method to that tonsorial madness. Ronaldo had injured a leg muscle before the semifinal against Turkey, and on the day leading up to the game he didn’t want to speak about it with the rabid Brazilian media. “So I did the haircut,” he says. “I saw my teammates and asked, ‘Do you like it?’ They said, ‘No, it’s horrible! Cut this off!’ But the journalists saw my haircut and forgot about the injury.” The next day Ronaldo shook off his leg knock and scored the goal that sent Brazil to the final.

Ronaldo shares another tale from the World Cup that sealed his place in history. Four years earlier, on the day of the 1998 final outside Paris, Ronaldo had taken a post-lunch nap during which his body convulsed into seizures, and he had barely any influence on the game in France’s surprising 3–0 victory. In Japan, though, Ronaldo had a different plan. After lunch on the day of the final, he says, “I was walking the corridor looking for someone . . . to talk to me so I wouldn’t sleep, to not give me the chance to have it happen again. I found [Brazil’s backup goalkeeper] Dida and I said, ‘Dida, please stay with me. . . . Talk to me.’ And he was with me until we left in the bus for the stadium.”

In some ways, Ronaldo became even more beloved once he was exposed as vulnerable, human. But it wasn’t always that way. In the late 1990s, back when kids still put posters up on their walls, the Italian tire company Pirelli produced a classic of the genre: Ronaldo, arms stretched wide in imitation of Christ the Redeemer, the statue that overlooks Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro. For Christians around the world, that image represents divine salvation. These days, when Ronaldo mentions salvation it’s usually in the context of keeping Real Valladolid up in Spain’s first division. It’s worth noting: He uses that positive term instead of the one associated with failure, relegation. “For now,” he says, “we still have to fight for salvation.”

Ronaldo is no longer capable of conjuring goals that no other human could imagine. But he’s tapping into another trait that has its own intrinsic value. “I’m kind of born for work, for producing,” he says. “I really don’t care if people remember me as Fat Ronaldo or Ronaldo Fenômeno. I did my best in everything I could. It was a great career, and now I’ve started a new one. And I want to be the best at that career, too.”

What’s in a name? If he can pull this off, someday OG Ronaldo could also be known as Boardroom Ronaldo.

Comments

Post a Comment