New on Sports Illustrated: The Lost-and-Found Story of Michael Neustifter

A battle with his vision almost derailed Michael Neustifter's baseball career. He still has a path forward.

The renowned specialist in Nashville held the tests results on the 21-year-old college third baseman seated in front of him. The patient’s mother sat next to her son. The doctor ruled out any structural abnormality of the eyes. He could diagnose only one reason why this otherwise healthy young athlete suddenly was losing his vision.

“There is this very, very rare condition called visual snow syndrome,” the doctor said. He opened a reference book to the pages describing the condition. “All these symptoms match up with what you’ve been experiencing.”

The next words out of the doctor’s mouth would change the young man’s life.

“I’m sorry. There is no cure.”

***

Sometime this summer Major League Baseball will conduct an ad hoc version of its amateur draft. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, which halted all baseball since mid-March, it

may be shortened from its usual 40 rounds to between five and 10 rounds.Players under consideration by major league teams include the usual assortment of comeback stories, such as pitchers recovered from Tommy John surgery or position players coming back from broken bones, torn hamstrings or poor seasons.

Few if any of the comeback stories will have covered as trying a physical and emotional arc as the one of Michael Neustifter of North Greenville University in Tigerville, S.C.

“That was a real blow after leaving that doctor,” he says. “I thought I played my last baseball game. I could probably live a somewhat normal life with what I had. Unfortunately, I play a game where the eyes are probably the most important tool.”

This is a lost-and-found story. It is a story that befits the times of this pandemic, when life as we knew it and all we took for granted are taken away, and when our greatest coping mechanism is hope.

“Patience was never a great virtue of mine,” says Michael’s mom, Angela. “I learned a great deal about patience and what true faith is, which is believing in something you can’t see.

“That sounds like a play on words because we were dealing with a vision issue. You think you have faith until something like this happens. Then it goes to a whole different level. It has affected the way I view things and will the rest of my life.”

***

“Come to the dugout.”

It was Feb. 15, 2019, a Friday night, when Angela saw the text from Michael on her phone. Angela was visiting Michael for the weekend from the family’s home in Carrollton, Tx. Michael’s father, Dan, a contractor for the Dallas County Juvenile Department, had scheduled to make the trip, but a work assignment prompted Angela to go instead. When she received the text, Angela was in the stands watching North Greenville play Nova Southeastern.

“I knew something was wrong,” she says. “As a baseball mom, I know you never go to the dugout during a game.”

Michael had batted four times in the game and struck out three times. In the past three games he was 0-for-8 with three strikeouts. Worse, his bat was not coming close to making contact with the baseball. Having played his first two seasons at Oklahoma State, where as a sophomore he hit .299 and was named Second Team All-Big 12 Conference, the 6-foot-3, 215-pound third baseman had never struggled like this.

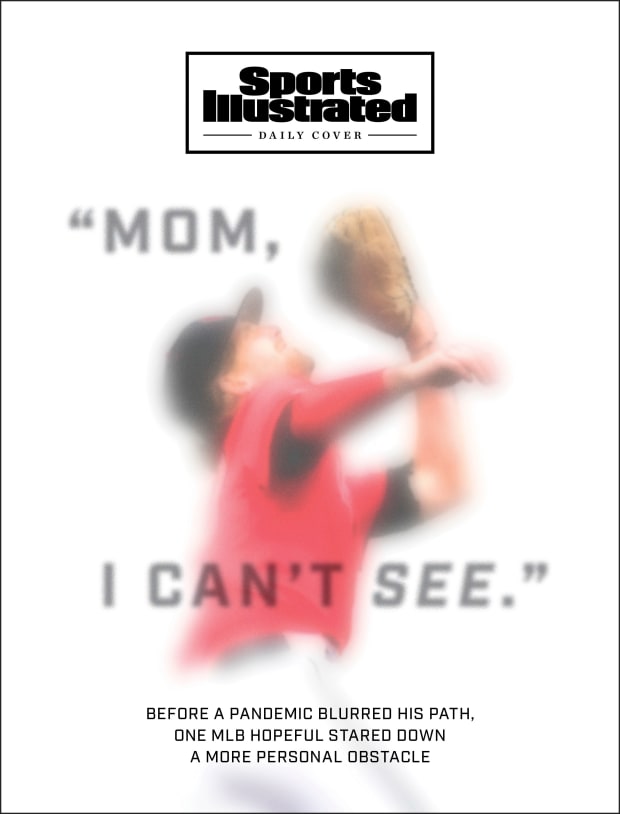

“Mom, I can’t see the baseball,” he told Angela.

“Don’t worry,” she says. “It’ll be better tomorrow. That’s baseball.”

“No, Mom. I can’t see. Like, I can’t see!”

Staff from North Greenville, a Division-II school, already had called ahead to the emergency room at Greenville Medical Trauma Center.

“I was thinking maybe I can play the next game,” Michael says. “Little did I know it was so much more.”

Doctors at the emergency room examined his eyes. They ran some tests. They told Michael it appeared he had a detached retina. Michael and Angela decided to see an eye specialist Monday morning. When they did, the ophthalmologist ran another battery of tests.

“I promise you, you don’t have a detached retina,” the doctor said. “There’s nothing physically wrong with your eyes.”

“Well, I can’t see anything clearly,” Michael said.

“Well, I don’t see anything,” the specialist said. “I can’t tell you what’s wrong if I don’t see anything.”

Angela, a freelance court reporter, extended her stay. For the next nine days she drove Michael from doctor to doctor, eventually driving through a snowstorm to get to a specialist in Nashville. That’s when they received the diagnosis of visual snow syndrome, or VS.

VS is a devastating and rare neurological disorder that can affect vision, hearing and cognitive function. Michael’s symptoms fit those of VS. The world to him looked like a broadcast on an old television set marred by terrible reception—with blurry, visual snow, like static that never stops, not even when his eyes were closed. VS patients never get relief from the condition. There is no procedure to correct it. No cure. The condition is so rare that its prevalence is unknown. Its onset occurs among a younger population than most neurological disorders.

The symptoms can remain stable, but for some people they worsen. The worst cases do not lead to total blindness but can become severe enough to meet the legal definition of blindness.

“It made sense,” Michael says of the diagnosis. “It was hard to gather it in, but it made sense.”

After nine days with Michael, and many sleepless nights, Angela booked a flight home to Texas.

“I had held it together for nine days to get through all the doctor visits,” she says. “I don’t even remember getting to the airport. It was like I was in a daze. I was leaving Michael a thousand miles away. As I got to the gate, I just put my head in my hands and the tears just … it’s hard to talk about it now.

“I remember sitting there at the gate and tears just began to stream down my eyes. I said, ‘God, take my vision.’ As a parent, you would take on anything for your child.”

Michael kept hope that the blurry vision would go away. He attended practices and games, but he could not see well enough to play. Finally, his coach, Landon Powell, advised him to take a medical redshirt. His season officially was over.

“That was like throwing in the white flag,” Neustifter says. “That was probably my lowest point. Once that happened, it all kind of hit me. ‘Oh my gosh, I might never play baseball again.’ ”

Powell is a former major league catcher who caught the perfect game of Athletics pitcher Dallas Braden 10 years ago on Mother’s Day. He could empathize with Michael’s anxiety over the onset of a sudden medical condition. In 2008, at age 26, Powell suddenly felt ill, lost his appetite and showed signs of jaundice. Doctors at first were confounded. They eventually diagnosed Powell with autoimmune hepatitis, a genetic disorder that causes his immune system to attack liver cells. He made his major league debut four months later.

In 2013, Powell and his wife, Allyson, lost a daughter, Izzy, five months old, to another rare autoimmune disease, Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). The couple also started a charity event, Donors on the Diamond, in 2010. Powell also serves on the board of directors of Donate Life SC, an organization that promotes organ, eye and tissue donation.

“The support Michael received was unprecedented,” Angela says. “We could not be more grateful for the way Coach Powell and everybody supported him. He was at the place he needed to be. I’m just convinced there are no coincidences in life.”

Upon returning home, Angela says she slept “for two or three days solid.” Then she began researching as much as she could about Michael’s condition.

“I began calling all over,” she says. “I called between 30 and 40 doctors. Switzerland, Panama, all over the United States … I had to think outside the box. I did not believe he had that [VS] condition.”

One day Angela visited her family physician for a routine checkup. He could see she was stressed. He asked her what was wrong.

“I broke down and told him what was going on,” she says. “He prayed with me. Then he said, ‘I want you to call this doctor, Dr. Charles Shidlofsky.’ Of all the research I had done over several months, I did not know this doctor. It turned out he was five miles from our home.”

When Michael came home from school in mid-May, he made an appointment with Shidlofsky, an optometrist in Plano, Texas.

“The first thing I noticed is he ran these different tests,” Michael says. “I had been to so many different doctors, and they all ran the same tests.”

Says Angela, “These were 20 to 30 tests that had nothing to do with dilating the eyes. He even ran an MRI to make sure something wasn’t going on in the brain. He was checking the neurotransmissions from the brain to the eyes and back. It was four hours of testing, and then another four hours of testing a second time.”

Finally, Shidlofsky arrived at a conclusion.

“You don’t have visual snow syndrome,” the doctor told Michael. “I think that was misdiagnosed. What I’m seeing is you had a concussion in the past six or seven months that you probably didn’t know you had. Concussion is a form of brain damage, and when it’s not treated properly you can have serious side effects. I’ve seen it many times, often with football players.

“You just have some messed up pathways between the brain and the eyes, and they are messed up because you were not treated properly.

“I will have your vision back to where it was by the end of the summer. It may even be better than what it was.”

Michael and Angela could hardly believe what they heard.

“It wasn’t like anything in the movies,” Michael says of his reaction. “It took some time to process. It wasn’t promised that I was going to get my vision back. We were optimistic. It was just that now we had hope after being shut down by so many doctors. That was the big thing.”

Says Angela, “I think we saw 11 doctors in four different states. As it turned out the one who cured his vision was five minutes from me.”

The diagnosis made Michael remember an incident from a game on Feb. 2, 2019. In trying to stretch a double into a triple, Neustifter banged his chin on the ground when he slid headfirst into third base. He was called out. As he jogged off the field, he saw stars floating around him. He had trouble breathing. He felt nauseous. He stayed in the game.

When Michael and Angela returned to their car after the diagnosis, they looked at each other in silence. They didn’t know what to say. Finally, Angela took her son’s hand and said, “Before we say anything, we need to say a little prayer to the Lord and thank Him for giving us hope.”

Over the next 10 weeks, at home and at the doctor’s office, Michael performed a series of eye exercises designed to rebuild the pathways between his brain and eyes. So grueling were the exercises that at first they made him nauseous. He played part-time for a local summer league team.

“The first time I saw the ball coming at me I thought, That’s what the ball is supposed to look like,” he says. “The fall was a struggle, but I kind of anticipated it. Coach Powell told me, ‘Just keep working at it every day. You’re my guy. I trust you.’”

In the spring, Neustifter hit .296 in his first seven games. Then in a weekend series against Kentucky Wesleyan, he homered in three straight games while driving in 11 runs. He knew then he was all the way back.

He was hitting .315 and slugging .641 when the pandemic ended North Greenville’s season on March 12.

“It wasn’t as negative as many people thought,” he says. “A lot of guys were like, ‘You must be so [ticked] after everything you’ve done.’ Listen, all of us were devastated that the season ended so abruptly. But after everything I went through, I know the Lord has a bigger plan for all of us. I put my trust in Him. I’ve been here before.”

Neustifter has remained at North Greenville to continue baseball training. The draft this year is harder to predict than usual. Major league teams have little fresh information on players because of the shutdown of high school and college baseball. The NCAA has granted another year of eligibility for college players. Many players may want to return to school to increase their value. Teams will have fewer picks and less money to spend. Undrafted players cannot be signed for more than $20,000, down from the $125,000 limit before it counted against a team’s allotted pool of bonus money. Neustifter, who still has two years of college eligibility, is eager to begin what has been a childhood dream to play professional baseball—even if it means signing as an undrafted free agent.

“That’s what I want to do,” he says, “especially this draft. It’s looking like no one is getting a lot of money. That’s kind of out of the question. I’ve dreamed of just getting the opportunity.”

One baseball season ended by near-blindness. The next season ended by a pandemic. Even without a pro contract, Neustifter has provided a story for these uncertain times.

“Hope, that’s the big thing,” Michael says. “I’ve had people reach out to me, people I don’t even know. They say, ‘I love how you just kept up hope.’ With the situation the world is in right now, a lot of people need to hear that.

“I hope that people can find some hope in my story. And it may not even be physical problems that they need help with. Just finding hope is a powerful message.”

Comments

Post a Comment